“The most important thing to me is figuring out how big a moat there is around the business. What I love, of course, is a big castle and a big moat with piranhas.” – Warren Buffett

A business is ultimately worth its ability to build and protect cash flow. In the venture world, growth often steals the show while durability takes a back seat. Investors and entrepreneurs would do well to think hard about current and future moat, even at the early stages. It should be a critical consideration in deciding which opportunities to pursue and how to allocate precious resources. The proverbial business graveyard is full of fast growers that didn’t sustain.

So how do you evaluate how big a moat there is or will be? I recently came across this excellent report which seeks to answer just that. While the scope of the report is broader than software, the concepts are transferable and for the most part, timeless.

Below I’ve cherry picked a couple concepts that particularly struck me as either unfamiliar or non-obvious. I highly recommend skimming the full report for a more complete perspective on how to think about moats.

1) Pricing power > cost advantages

Most comparative advantages can be divided into two buckets: consumer advantages and production advantages. Here’s an easy way to think of it:

- Consumer advantage: can charge a premium without getting undercut

- Usually appears in the form of high gross margins

- Comes from things like brand, switching costs, network effects, and intellectual property

- Production advantage: can undercut price while maintaining attractive margin

- Usually appears in the form of high asset turnover (revenue / assets)

- Comes from things like process complexity, access to scarce resources, and scale economies

Here’s the interesting point: evidence suggests that differences in customer willingness to pay (pricing advantage) account for more of the profit variability among competitors than disparities in cost levels (cost advantages). Translation: pricing power > cost advantages. A separate study by Raynor and Ahmed identified two essential rules followed by superior performing companies after controlling for “random luck”: better before cheaper and revenue before costs. I believe this holds especially true for SaaS businesses (more on this below).

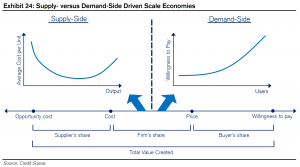

Supply side returns to scale (i.e. unit costs) eventually level off and/or reverse due to bureaucracy, complexity or input scarcity. On the flipside, positive feedback on demand have no such point of diminished return. Basically, there is a downward limit on unit costs while there is no upper limit on price premium. The chart below illustrates this concept.

Granted, this chart was probably created with more traditional industries in mind. So this got me thinking: how does this apply to B2B SaaS businesses? Well, the key input costs (i.e. the costs to produce and deliver product) are fairly standard across firms, primarily comprised of people (R&D, customer success) and hosting (e.g. AWS or Azure). So where is the supply advantage to be had? Holding execution constant, I’m not really seeing it.

The action is in the price. Look back at the factors for consumer advantage above. Network effects, switching costs, IP and brand all come into play. Additionally, experience goods tend to have more pricing power than physical goods. SaaS businesses would do well to focus more on building “price moat”.

2) Exit costs is a better way to think about entry barrier

I love this reframing because it is more complete. Unlike entry barriers which just focus on the upfront cost to enter the game, exit costs also incorporate the idea of transfer-ability of assets or – in startup lingo – the ability to pivot. Railroad tracks, for example, are expensive to lay, hard to move and can pretty much be used for one thing. Airline routes, by comparison, can change easily. Airlines can choose to not compete for certain routes, whereas railroads must fight to the death for their routes. The same concept can apply to intangible assets like brand (I doubt Harley Davidson mini-vans would fly off the lot, despite Harley’s substantial brand investment over the last 50+ years).

High exit costs should discourage new entrants, not only because of the upfront cost to enter the game but also because of the lack of optionality if demand flops or competition heats up.

Let’s take Magic Leap – the cutting edge augmented reality company – as a tech example. The capital invested to date is staggering (I lost track of the billions), especially considering it hasn’t generated any revenue to speak of. And it’s no secret the product hasn’t taken off. Dumb investment, right? Maybe, but maybe not. When the investors evaluated the opportunity, I’m quite certain they took some comfort in the significant optionality attached to the asset. The use cases for this unique technology are virtually limitless. Now – low and behold – after its consumer entertainment application flopped, the company has pivoted to a productivity use case focused on the enterprise market. There is still more story to be written, another chance at glory. Whether it ultimately succeeds or not, Magic Leap is not railroad tracks.

When deciding which opportunities to pursue and where to allocate resources, entrepreneurs would do well to consider upfront cost and optionality down the road.

Footnote:

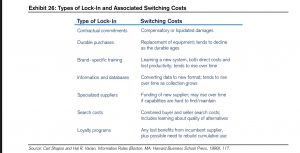

Regarding pricing power – specifically switching costs – I found the chart below quite useful. There are many more types of switching costs than meets the eye!